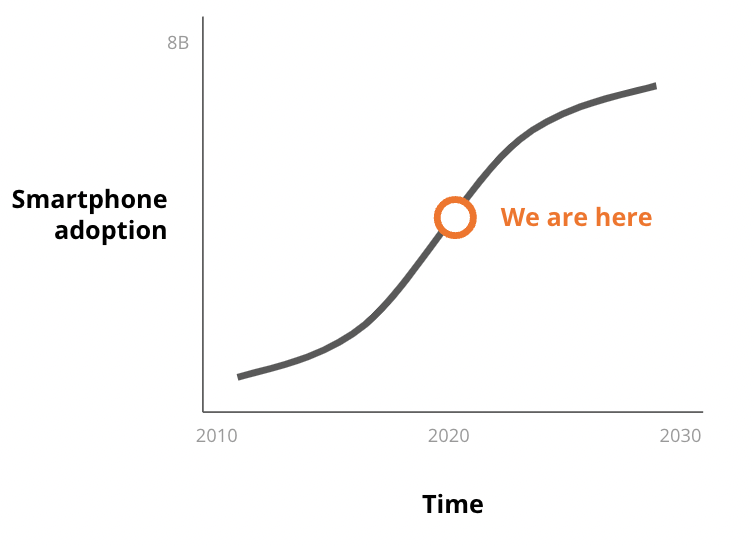

Another billion people will soon get their first smartphone. Who are they and how do we build useful products for them?

The next billion

The world is getting a smartphone fast: today 4 billion people own one, that’s 1 in 2 people alive.

This also means another 4 billion people don’t yet have one. How should we think about this group? They can be split by demographics of age and income, which highlights two major frontiers:

- Age frontier: the young who reach an age at which they get their first smartphone

- Economic frontier: people at lower income levels for whom smartphones get within reach (increasing incomes, decreasing smartphone prices)

Despite economic setbacks from COVID, both frontiers should be expected to push forward and reach about 1 billion new people each in the next 7-8 years.

Age frontier

This frontier, consisting mostly of today’s pre-teens, will give rise to many new behaviors & preferences foreign to us, natives of worlds rising post TikTok and Fortnite. Luckily, young people with smartphones are a group we can get familiar with day to day, through our kids, nieces & nephews, etc.: we can to a decent extent learn by carefully observing our surroundings.

Economic frontier

The economic frontier is more distant to people building technology: the overlap between product teams and the world’s lower income demographics is small. The products we use every day, giving us access to information, entertainment and communication, often don’t work well — how do we build useful products for them?

My years of building

I’ve led a number of products working in Google’s Next Billion Users organization, including Camera Go (a high quality camera for low cost smartphones), Kormo (a job matching platform for semi-skilled work), Files by Google (a fun, popular smartphone cleaner) and smaller / early stage initiatives. While the local differences and complexities can be overwhelming, over time some helpful patterns and processes emerged.

Understanding the next billion

A billion people is by definition hugely diverse. Geographically, we see this group coming online in places as far dispersed as India, Brazil and Nigeria, but there are some broad stroke commonalities: a typical household income might be $400 per month, an average household might consist of 5 people (vs. 2 in The Netherlands where I’m from), English literacy is often present but to lower degrees.

While stuck at home, the website Dollar Street can give a visual glimpse of people in this demographic and how they live.

In our research around the globe, often focused on new smartphone users, we see a range of recurring behaviors and characteristics. The next billion..

- use entry level smartphones (new for say $80) or older ones

- step up from feature phones with a keypad (some internet enabled)

- often share phones with family members

- rely on teachers (family members, shop owners) to help them navigate their phone

- have finite data access (no home Wi-Fi, mobile data caps, less coverage)

- often have limited literacy in their phone’s language

- have a preference for tapping and speaking over typing

- have a preference for video content

- run their small business using chat apps and social media

- often rely primarily on friends and family for information

Generalizations, but I find they all have enough general validity to be useful.

Looking at India

My team is deeply rooted in India, with many members and leaders born and raised there. Some work in India, and those located elsewhere (e.g. US, Singapore, Australia) tend to visit India frequently on research trips.

India has 1.4 billion people, 22 major languages (13 scripts), spans 3000 km from North to South and 3000 km from East to West — as a European, I’d consider it a large continent. I’m by no means an expert on India, but it’s the developing market I’m most familiar with and home to a large share of the next billion users.

Reverse innovation

You could say most of Silicon Valley builds products for the Bay Area and then adapts them for the rest of the world, while we build products for India and then do the same. The diversity in India helps build products that generalize better than you might expect: we often see our products take off globally, starting in developing regions, then spreading to developed markets, a concept called reverse innovation.

Reverse innovation tends to work remarkably well as products built for resource constrained environments often have universally desired qualities: low cost, reliable, easy to use. Also, the diligence put into understanding people’s problems and environments — needed when building for unfamiliar demographics — results in solutions carefully crafted with the human experience as the focal point.

Going local

To do this, our product ideation & build process are heavily driven by local research.

Observing

First we try to uncover problems, looking at market research (reports and data) and — more importantly — ethnographic research (local observations), shadowing people in their daily lives and interviewing them, attempting to answer questions such as:

- How do people talk about the role of smartphones in their lives?

- How do smartphones fit (and misfit) in established customs?

- Which products and apps are gaining traction?

- How do people use these products?

- What problems do we observe around their use?

- Which products don’t gain traction / which behaviors remain offline?

Honing ideas

Based on this, we lay out product ideas. For example: a simple, fast camera that can translate text. We go back and test these as flash cards, drawings, or as a pretotype (pretend product) on a smartphone. Do we see enthusiasm? Can people describe how it fits in their lives?

Prototyping

If we find a promising idea, we build a working prototype and test it, recruiting a few hundred people in for example schools or malls. We get more opinions and aggregate usage statistics, helping uncover patterns:

- What’s the frequency with which they use the product?

- Do they like it enough to share it with friends?

- What parts do they use most?

- What parts are used less?

- What parts are causing problems?

- How do they describe the product to us?

- What feature requests are we getting from them?

We iterate a few times on the prototype. Once testers are enthusiastic enough about the prototype that they want to keep it, we go heads down and start building the full product.

Not-so-usable

Building products that are easy to use for new smartphone users is hard: people don’t understand all the text, can’t find the right button, struggle with swiping, etc.

Phones tend to be set to English even if people are not native speakers. Non-latin scripts are notoriously tricky to type. Abstract paradigms such as app switching are unknown and icons often unrelatable or misinterpreted.

If lucky, new users have a savvy sibling that teaches them, or they pay a neighborhood shopkeeper to explain and set things up.

It takes many rounds of trial & error, but luckily there are some helpful design principles:

- Rely on both visuals and text (not just one)

- Use words that are used in everyday life

- Use visuals of easily recognizable items

- Use speech (input & output) as an option where possible

- Proactively suggest language switching

- Use animation & color to add clarity

And importantly: keep the product super simple. This is hardly a new insight, and I don’t believe designers ever forget about it. Simplicity just requires a lot of work. For more on designing for this demographic, check out Designing for Digital Confidence.

Building for a billion

Another billion people will get their first smartphone soon, but in contrast to the first few billion smartphone users, they tend to be less like those that build their products. In building for them we need to put assumptions aside and learn, research, observe and listen to users, iterating and crafting together with them. With smartphones holding so much promise, it’s an important challenge to get right. Let’s build!